In today’s world of Theo Epstein’s using advanced statistical metrics to arrive at the best players to win a world championship, you would think there’s just as much thought given to everyone’s favorite mutual fund metrics – the Morningstar rating. After all, there’s billions and billions of dollars basing their decisions to invest in this mutual fund over that based on those rankings. Only, they don’t do such a good job of helping find the best players for your future team. At least that’s the claims The Wall Street Journal are making about Morningstar’s ranking system this week.

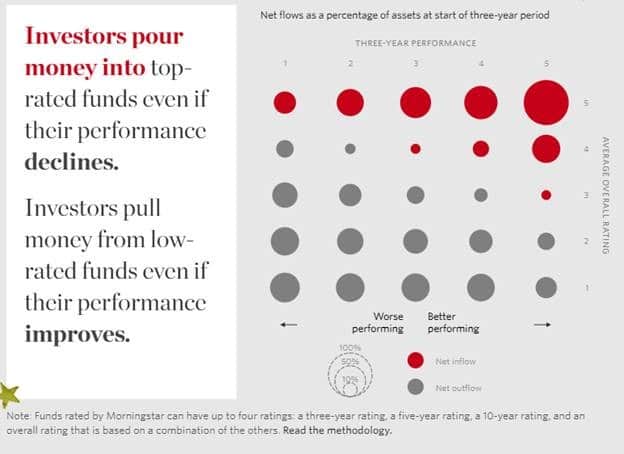

The article gives example after example of pensions and financial advisors investing into funds with a five star rating from Mornginstar, only to see the performance dwindle afterwards. There are quotations of financial advisors admitting to recommending funds to clients purely based on the star rating; there are charts showing funds not staying at five stars over time; and there are charts showing investors pulling money from low rated funds while performance is actually improving. Here are some interesting bits of information from the long form article:

Of funds awarded a coveted five-star overall rating, only 12% did well enough over the next five years to earn a top rating for that period; 10% performed so poorly they were branded with a rock-bottom one-star rating.

Morningstar groups funds into categories based on their investing style or area, more than 100 groups in all. It compares funds not to all other funds, nor to the overall market, but to other funds with the same investment focus. The top 10% of funds in each group receive five stars, the bottom 10% get one, and the rest get two, three or four stars.

The ratings don’t reflect raw performance, but performance adjusted for funds’ degree of risk. To make that calculation, Morningstar uses an algorithm Mr. Mansueto devised that reflects the variation in funds’ month-to-month returns.

To Morningstar’s defense there is quotation after quotation from Morningstar ensuring that these rankings shouldn’t be used as an end all be all but as a way to narrow down a list of potential investments (despite the fact that there’s story after story suggesting that’s the what financial advisors use it for). The entire premise of the Wall Street Journal Investigation is to say that Morningstar’s system is bad at predicting how mutual funds will perform in the future. To that, we say duh. They can only rank funds based on past performance. If their statistical data could predict futures results, everyone would be rich. But alas, it seems the star ranking matters more to an investor and advisor than the returns themselves. Example A:

So, is it Morningstar’s fault for not being explicitly clear that these stars are just a starting point when looking to invest, or is it the financial advisors and investors fault for using the stars as the only due diligence before investing? We say both. Morningstar clearly knew what was happening despite their warnings, and built their brand as the place billion and billions of dollars go to find an investment. However, Financial Advisors are also the blame, with it clear from the numbers that they should have done better due diligence. Ultimately, they trusted a brand to do their jobs for them.

Morningstar doesn’t have a crystal ball, even if they claim their top star programs “likelier to outperform in the future.” After all, past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. And doing these types of rankings are hard. As we say in our Managed Futures Rankings:

It’s trickier than it looks. Put too much emphasis on returns, and you penalize those who control risk. Too much emphasis on experience and you penalize a potential new star. Too much reliance on the present and you discount the past, too much on the past and you discount the present, and so on.

You see, if not for any rankings, you would have these advisors likely just going to the best performing fund last year. The rankings aren’t all the predictive, but neither is the de facto ranking of performance only. It would be interesting to see the Morningstar rankings alongside a simplistic look at persistence among the top quartile funds, or how the top ranked five star funds do against their benchmarks. And would be great to see Morningstar sort of Epstein their rankings to incorporate more data and more time frames. Here’s how we do that in our ranking methodology:

We measure the programs across different metrics related to return, risk, correlation levels, and length of track record. Next, we time-weight the numerous statistics, evaluating each metric across 1, 3, 5, and 10 year time periods in addition to the full length of the program since its inception. This focus on varying time frames ensures that great returns far back in a program’s track record don’t skew their ranking, and, likewise, that newer programs that haven’t “lived through tough times” don’t dominate the rankings.

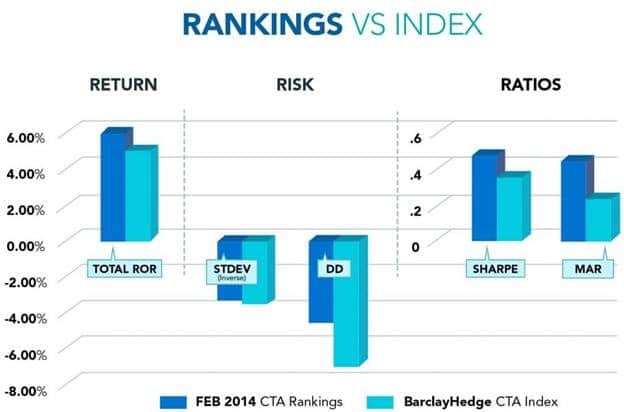

But rankings are only as good as their ability to identify funds/programs which can outperform their benchmarks – be it on returns or risk, or risk adjusted returns. So how have our rankings done in that regard? Here’s a look at an equal weighted portfolio of the Top 15 as displayed in our February 2014 rankings, and how it has performed against the benchmark BarclayHedge CTA Index over the 3 years following those rankings release:

(Disclaimer: Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results).

(Disclaimer: Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results).

So what do you say Morningstar… should we partner up on a new, more advanced, way to do your rankings? Two Chicago companies working together to meet the criticisms levied by the WSJ piece and launch a new ranking methodology to meet the new statistical/quant age we now live in. Helping advisors instead of hiding behind the disclaimer that these aren’t really supposed to be used to base allocation decisions on. Call us at 855-726-0060 to talk. And check out how we do it by downloading our Managed Futures Rankings here.